Thomas Fountain Blue

The Reverend Thomas F. Blue, the nation’s first African-American to head a public library, was a respected leader in the civic, religious, and educational life of the Louisville black community.

The son of former slaves, Blue was born in Farmville, Virginia. Upon graduating from Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in 1888, he gave a farewell address in which he urged his classmates to “let our every movement be characterized by unity of aim, unity of purpose and unity of act; then and not until then will the dark cloud of ignorance, superstition, and intemperance disperse, and education, intelligence, and virtue spread over our land.”

After teaching school in his native Virginia, he earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1898 from Richmond Theological Seminary. He went to work as a secretary of the YMCA, serving Spanish-American War soldiers. He then moved to Louisville to work as secretary of the YMCA from 1899 to 1905.

On September 23, 1905, Blue when was chosen to head the Louisville Western Branch Library, the first public library in the nation to serve African-American patrons with an exclusively African-American staff. What began in three rented rooms of a private residence in Western Louisville moved in 1908 into a dedicated Carnegie building, which has become a Louisville landmark at the corner of 10th and Chestnut Streets. In 1914, Mr. Blue opened Louisville’s second Carnegie branch library for African-Americans -- this time in Eastern Louisville.

In 1919, with the addition of the two new branches, a “Colored Department” was created, the first example of such an organization in any public library system in the United States. Blue was made head of the department which included eight assistants. In addition to the two Carnegie branch buildings, this Department included two junior high schools, 15 stations and 80 classroom collections in 29 buildings -- a total of 99 centers for the circulation of books for home use in 46 buildings in Louisville and Jefferson County.

Although Rev. Blue spoke of himself as “untrained, like Dewey was untrained,” his most far-reaching work was the creation of an apprentice class for those wanting to enter library service. Blue’s class drew students from as far away as Houston and led to the establishment of the Hampton Library School in Virginia. From 1905 until his death 30 years later, Rev. Thomas F. Blue served the Louisville Free Public Library, achieving national recognition as a pioneer in the field of public service.

Rachel D. Harris

Rachel Davis Harris (1869-1969) became the first African American woman director of a public library branch in Kentucky when she was appointed in 1935. Previously, she was the children's librarian at the Louisville Western Colored Branch Library and later the manager of the Eastern Colored Branch Library. A native of Louisville, Mrs. Harris graduated from Central High School in 1885 and was a teacher for eighteen years in the city's schools.

In 1905, Louisville saw the opening of the first free public library for African American readers staffed and operated entirely by African Americans. Reverend Thomas Fountain Blue (1866-1935) was appointed as the branch's director, while Mrs. Harris and Ms. Elizabeth I. Finney were hired as his assistants. In 1912, Rev. Blue started a library training program for African Americans.

In January 1914, Mrs. Harris was appointed as the branch manager of the new Eastern Colored Branch. In 1927, she and Rev. Blue attended the first Negro Library Conference in Hampton, Virginia. In 1935, she succeeded Rev. Blue as the new director of the Louisville Public Library Colored Department upon his death. She served in this role until her retirement in 1942.

Mrs. Harris passed away in 1969 and is buried in Louisville Cemetery.

Sources Cited:

- "November 24, 1935 (Page 7 of 64)." The Courier-Journal (1923-2001) Nov 24 1935: 7. ProQuest. 29 July 2019 .

- Fenton, M. (2014). Rachel Davis Harris and the Colored Branches of the Louisville Free Public Library, Louisville, Kentucky. [online] . Available at: http://littleknownblacklibrarianfacts.blogspot.com/2014/04/rachel-davis-harris-and-colored.html.

Joseph Seamon Cotter Sr.

Joseph Seamon Cotter Sr. (February 2, 1861 – March 14, 1949) was a poet, writer, playwright, and community leader raised in Louisville, Kentucky (but born in Nelson County, Kentucky). Cotter was one of the earliest African-American playwrights to be published. He was known as "Kentucky's first Negro poet with real creative ability."[1] Cotter was born at the start of the American Civil War, and was raised in poverty with no formal education until the age of 22. He later became an educator and an advocate of black education.[2]

Cotter grew up in a family of mixed racial heritage. His father, Michael J. Cotter, was a white man of Scots-Irish ancestry, and his mother, Martha Vaughn, was a freeborn black woman of mixed heritage (one of several children born to an African slave mother and an English-Cherokee father).

On July 22, 1891, Cotter married Maria F. Cox, a fellow teacher, with whom he had four children: Leonidas, Florence, Olivia, and Joseph Seamon Cotter Jr (a distinguished poet-playwright in his own merit).

Joseph S. Cotter Jr.

Joseph Seamon Cotter Jr. was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1895 and was raised in a family with a strong tradition of poetry. His father was an educator and poet, and the family was friends with the prominent poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Cotter showed literary talent from an early age and was particularly fond of Keats.

He attended Fisk University for two years before contracting tuberculosis and returning home. He wrote extensively and published one collection of poetry, The Band of Gideon, before his death in 1919 at age twenty-three.

Cotter rejected the popular dialect style of his time and wrote about the impact of World War I, displaying empathy for the experience of black soldiers and addressing the issue of racial injustice.

Source: Fall 1989 University of Georgia Press Catalogue, p. 27

Recollections

Life as a Slave: The Story of Mrs. Julia King of Toledo, Ohio

Prepared by the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for the States of Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Virginia and Tennessee Narratives

Although the records of the family were destroyed by a fire years ago, Mrs. King places her age at about eighty years. Her husband, Albert King, was the first Negro policeman employed on the Toledo police force. She was the first colored juvenile officer in Toledo. Mrs. King, whose hair is whitening with age, is a kind and motherly woman, small in stature, pleasing and quiet in conversation. She walks with a limp and moves about with some difficulty.

Before her marriage, Mrs. King was Julia Ward. She was born in Louisville, Kentucky. Her parents Samuel and Matilda Ward, were slaves. She had one sister, Mary Ward, a year and a half older than herself.

She related her story in her own way:

"Mamma was keeping house. Papa paid the white people who owned them, for her time. He left before Mamma did. He run away to Canada on the Underground Railroad.

My mother's mistress -- I don't remember her name -- used to come and take Mary with her to market every day. The morning my mother ran away, her mistress decided she wouldn't take Mary with her to market. Mamma was glad, because she had almost make up her mind to go, even without Mary.

Mamma went down to the boat. A man on the boat told Mamma not to answer the door for anybody, until he gave her the signal. The man was a Quaker, one of those people who says 'thee' and 'thou.' Mary kept on calling out the mistress's name and Mamma couldn't keep her still.

When the boat docked, the man told Mamma he thought her master was about. He told Mamma to put a veil over her face, in case the master was coming. He told Mamma he would cut the master's heart out and give it to her, before he would ever let her be taken.

She left the boat before reaching Canada, somewhere on the Underground Railroad -- Detroit, I think -- and a woman who took her in said, 'Come in, my child, you're safe now.' Then Mamma met my father in Windsor. I think they were taken to Canada free.

I don't remember anything about grandparents at all.

Father was a cook.

Mother's mistress was always good and kind to her.

When I was born, mother's master said he was worth three hundred more. I don't know if he ever would have sold me.

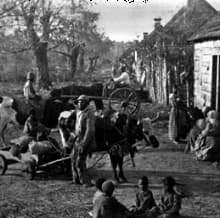

I think our home was on the plantation. We lived in a cabin and there must have been at least six or eight cabins.

Uncle Simon, who boarded with me in later years, was a kind of overseer. Whenever he told his master the slaves did something wrong, the slaves were whipped, and Uncle Simon was whipped, too. I asked him why he should be whipped; he hadn't done anything wrong. But Uncle Simon said he guessed he needed it anyway.

I think there was a jail on the plantation, because Mamma said if the slaves weren't in at a certain hour at night, the watchman would lock them up if he found them out after hours without a pass.

Uncle Simon used to tell me slaves were not allowed to read and write. If you ever got caught reading or writing, the white folks would punish you. Uncle Simon said they were beaten with a leather strap cut into strips at the end.

I think the colored folks had a church, because Mamma was always a Baptist. Only colored people went to the church. Mamma used to sing,

Don't you remember the promise that you made,

To my old dying mother's request?

That I never should be sold,

Not for silver or for gold,

While the sun rose from the East to the West?

And it hadn't been a year,

The grass had not grown over her grave.

I was advertised for sale,

And I would have been in jail,

If I had not crossed the deep, dancing waves.

I'm upon the Northern banks

And beneath the Lion's paw,

And he'll growl if you come near the shore.'

The slaves left the plantation because they were sold and their children were sold.

Sometimes their masters were mean and cranky.

The slaves used to get together in their cabins

and tell one another the news in the evening.

They visited, the same as anybody else.

Evenings, Mamma did the washing and ironing and cooked for my father.

When the slaves got sick, the other slaves generally looked after them.

I remember in the Civil War, how the soldiers went away. I seen them all go to war. Lots of colored folks went. That was the time we were living in Detroit. The Negro people were tickled to death because it was to free the slaves.

Mamma said the Ku Klux Klan was against the Catholics, but not against the Negroes. The Nightriders would turn out at night. They were also called the Know-Nothings, that's what they always said. They were the same as the Nightriders. One night, the Nightriders in Louisville surrounded a block of buildings occupied by Catholic people. Theuy permitted the women and children to escape, but killed all the men. When they found out the men were putting on women's clothes, they killed everything, women and children, too. It was terrible. That must have been about eighty years ago, when I was a very little girl.

There was no school for Negro children during slavery, but they have schools in Louisville, now, and they're doing fine.

I had two little girls. One died when she was three years old, the other when she was thirteen. I had two children I adopted. One died just before she was to graduate from Scott High School.

I think Lincoln was a grand man! He was the first president I heard of. Jeff Davis, I think he was tough. He was against the colored people. He was no friend of the colored people. Abe Lincoln was a real friend.

I knew Booker T. Washington and his wife. I belonged to a society that his wife belonged to. I think it was called the National Federation of Colored Women's Clubs. I heard him speak here in Toledo. I think it was in the Methodist Church. He wanted the colored people to educate themselves. Lots of them wanted to be teachers and doctors, but he wanted them to have farms. He wanted them to get an education and make something of themselves. All the prominent Negro women belonged to the Club. We met once a year. I went to quite a few cities where the meetings were held: Detroit, Cleveland, and Philadelphia.

The only thing I had against Frederick Douglasss was that he married a white woman. I never heard douglasss speak.

Jacob Aldrich

Prepared by the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Texas.

Jacob Aldrich, born January 10, 1860 in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, was a slave and grandson of Michelle Thiebedoux. He lived in Terrebonne and St. Mary's Parishes until the Mississippi River flood of 1928, when he came to Beaumont. He now lives at Helbig, a suburban community. He was rather well-dressed, his hat, clothing and shoes being in good condition, and indicating that they had been taken care of. His face was brown. Deep furrows run from the corners of his mouth, extending along the sides of his nose.

He related his story in his own way:

"Yessir, I was born in slavery, in 1860 -- January de tenth. I was born in Terrebonne Parish over in Louisiana 'bout twelve miles below Houma, but I lives in Helbig now.

My father's name was Alfred Aldrich, and my mother was name Isabella. I had five brothers and one sister.

De marster's name was Michelle Thibedoux. Dat was de same as Mitchell Thibedoux, and some of de people called him dat. He was my Gran'pa too, my mother's father. You know in dem times de women had to do what dere masters told 'em to do. If dey didn't pick on 'em and whip 'em. If she do what he want he stop picking on 'em and whipping 'em. Old Marster was bad 'bout dat, and his sons was bad too.

Marster would come 'round to de cabins in de quarters. Sometime he go in one and tell de man to go outside and wait 'til he do what he want to do. Her husband had to do it and he couldn't do nothing 'bout it. Marster was tough 'bout dat. He had chillen by his own chillen. Some of de marsters sell dere own chillen.

Marster was mean. He hardly ever whip 'em over dere clothes. He whip 'em on de bare skin. He make de women throw dere dress up over dere head, and make de men undress.

He didn't give us anything much to eat, and you better not steal. If you did he beat you. He give 'em a peck of meal a week. Each family git de same whether it was a big family or a little one. He give you corn meal. Sometime dey grind up oats and dy give you dat meal. Sometimes he give 'em pork.

My daddy was a ploy hand. Mother, she work in de field with a hoe. Marster used to work 'em from 'kin to can't'. It take a very severe rain to bring you out de field.

Marster live in a one-story plank house. He used to live by de S.P. Track at Shriever, but he got in debt. So he sold out and move to a smaller place. Dat was twelve year before freedom. Look to me like a man fix like he was with plenty of slaves to make his own living oughtn't have to let his place git away from him. But he gamble a lot. When he lost dat place he git de place down by Houma. Dat was a big place. I guess dere was twelve or fifteen hundred acres, swamp and all, but lot of it warn't cleared up.

Sometime Marster punish his slaves like dis. He had two heavy plank with a hole for your neck and two little holes for your wrists. Dey had a iron strap at de end to lock it down. Dey have another for your feet. Dey give you twenty-five licks and clamp you in it. Next morning dey give you twenty-five more and tell you to git your breakfast and git to work. Dey whip you with a half-inch bull whip. When dey git through with you, you need a doctor. How you 'spect anybody to rest in dat thing? Dey too sore to work. I seen dat thing since free time. Sometime dey put salt and pepper on your back after dey whip you.

Marster didn't look after de place hisself. He put his son to be overseer. He was all de time fooling with gals. He had as many mulatto chillens as his daddy had. He was my uncle.

He didn't want the slave boys to have anything to do with de gals. If he see a boy talking to a gal he call him and tell him he better not let him catch him talking to dat gal no more, if he did he gwinter beat him. If any man had told me dat, dey'd have to hang me. In Virginny where my pa come from dey couldn't hang a nigger. But dey hang him in Louisana where I was raised.

When a slave man want to marry he have to see de Marster. He tell him 'Yes', and tell de gal to go with de man and dat was de way dey marry on Marster's place.

The slaves had plank houses 'bout thirty-six foot. It hac a 'vision (division) in the middle, and one family live in each end. Dey had wooden shutter for window and door. Dey take planks and make bunks to sleep on like in a camp. The mattress was jis' old crocus sack with hay in it. Marster give 'em a sheet and quilt. Dey had a box for a table or maybe a rough shack table like what dey have in camps. Dey was benches for 'em to sit on. He give 'em a cheap tin plate and knife and fork.

Dere was 'bout twenty slaves, chillen and all. Dey had a special house for de chillen, and a old woman to take care of 'em. Lots of time dey put clabber in a trough and give de chillen a tin spoon and dey all crowd 'round de trough and eat it.

De slaves clothes was made out of bed ticking. Dat was better bed ticking den what dey has now. De chillen wore shirts dat come down most to dere feet. When dey went to work dey give 'em pants.

Marster kept three wimmin in de house for him. He sent all de way to Baltimore and bought a light one for him. She carry de keys up in de house where he live. Old Missus ain't say nothing 'tall 'bout it. Warn't no use, 'cause he a hard man.

De usual price for a common laborer in de field was eight or nine hundred dollars. Wimmen brought two hundred and fifty to three hundred dollars. But trained slaves was worth lots more. Lots of time a marster send a slave off to work in a blacksmith shop or some other kind of shop jis' to learn a trade, den when he come back he be de mechanic for de plantation. Dey train up wimmen dat way to sew and cook and sich.

I don't 'member nothing 'bout soldiers. Young Marster hide out and didnt' go to de war. He say 'round with de cullud folks in de cabins and sich. De white folks look down on him but dey 'fraid of him.

Old Marster die before freedom come. Officers come from Houma and told us we free. Dey had what dey call Military Law. Dey had a man to see after de plantation. Dey call him de Provo' Marshal.

After old Marster die dey used to hear de sugar mill running. When dey go to see 'bout it dere warn't nobody dere. It was old Marster's spi't. Heap of people don't b'lieve in ghos's but dey jis' as well to. Dere was a man what marry old Marster's daughter. Dey see him going 'round three months after he dead. Everybody say he going 'round 'cause he ain't at rest. She go and see de priest 'bout it. He say it going to take three massess to git him at rest. So she pay him for dem masses and den she satisfy.

Marster's main business was making sugar. Sometimes he work his slaves right 'long through Sunday. Sometimes he don't 'low de fires to go down 'til he git a hundred hogshead of sugar. Den after de crop was in and de sugar made, he give 'em a week off. He give Christmas day off. He give 'em a little dinner and whiskey. You got all you want at Christmas.

I spen mos' my time farming. I live in Terrebonne, den I move to St. Mary Parish. I left dere and come to Beaumont nine year ago. You 'member dat big washout they had back dere in 1927? Well, when de water went down I come here.

I think dat 'bout fix up my story."

I knew some others, too. I think Paul Lawrence Dunbar was a fine young man. I heard him recite his poems. He visited with us right here several times.

I think slavery is a terrible system. I think slavery is the cause of mixing. If people want to choose somebody, it should be their own color. Many masters had children from their Negro slaves, but the slaves weren't able to help themselves.

I'm a member of the Third Baptist Church. None join unless they've been immersed. That's what I believe in. I don't believe in christening or pouring. When the bishop was here from Cleveland, I said I wanted to be immersed. He said, "We'll take you under the water as far as you care to go. I think the other churches are good, too. But I was born and raised a Baptist."

(Interview, Thursday, June 10, 1937)