Today, libraries serve all of us -- the rich, poor, young and old. They show us where, collectively, we have been; as well as point the way to what we may become. Yet, there was a time in America when these doors of knowledge, culture, self-improvement and universal education were closed to people of color. When the Louisville Western Branch Library opened in 1905, it took its place in history as the first in the nation to provide library services exclusively for the African American community, using only African American staff.

For nearly a full century, the Louisville Western Branch Library has remained a separate and distinct flame: an unwavering source of individual self-enlightenment and a beacon of community strength and support.

Following the Civil War, despite constitutional amendments granting them freedom, citizenship and certain voting rights, African American desires for individual fulfillment and equality seemed unachievable. In the South, everything was legally segregated. And throughout the nation you couldn't find a public library which would dream of opening its doors of self-enlightenment to people of color. Most felt powerless to challenge the system. Yet in the late 1800's and early 1900's, African Americans in Kentucky -- in particular Louisville -- were among the leaders in a national struggle to address the injustices this system imposed.

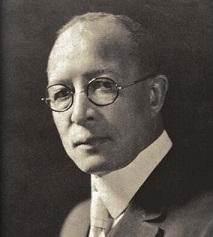

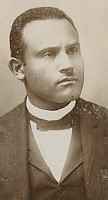

A growing population of African American readers helped spur a few individuals to challenge the 1902 legislation which created a free public library system in Louisville. One such person was Albert Meyzeek. During a temporary assignment as principal of Central High School, Meyzeek, concerned about the lack of adequate reference and reading materials at his school, argued persistently, and persuasively, to the City Library Committee that African Americans should have access to this proposed system.

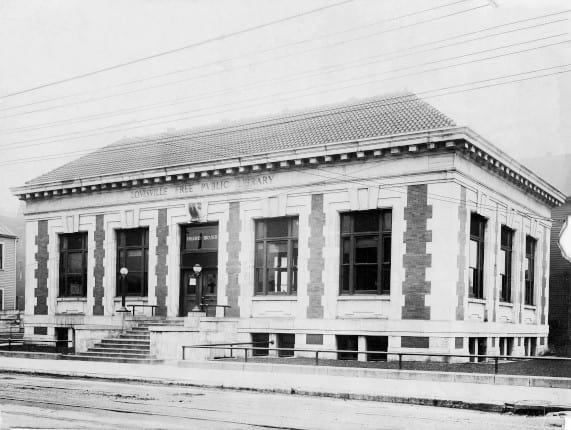

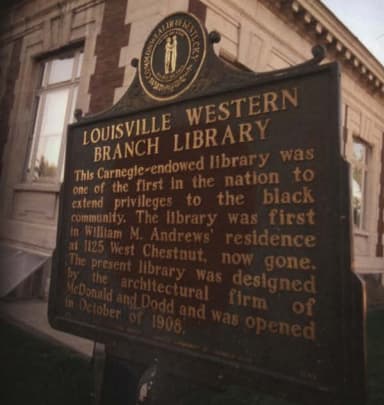

By the time the Louisville Free Public Library opened in 1905, its plan called for the establishment of a branch library for its "colored" citizens with funds already pledged by the wealthy industrialist, Andrew Carnegie. Until the Carnegie building could be completed, the City rented three rooms of a private residence at 1125 West Chestnut Street, in the heart of Louisville's predominantly black westside neighborhood.

Above the door was a sign which read, "Knowledge is power." Carnegie gifts were instrumental in erecting and furnishing a dedicated library building which opened in 1908 on the Southwest corner of 10th and Chestnut Streets.

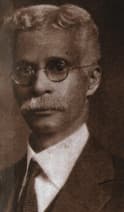

The Reverend Thomas Fountain Blue, a native of Virginia who had been educated as a theologian at Virginia Union University, was chosen branch librarian. The nation's first African American to head a public library, created a high quality operation which the community and the library authorities declared was a success from the beginning. The Louisville Western Branch Library, a separate African American facility independently staffed by African Americans to serve its citizens fostered a feeling of "perfect welcome, pride in ownership and unqualified privilege.

"The library does more than furnish facts and circulate books. With its reading and study rooms, its lecture and classrooms, it forms a center from which radiates many influences for general betterment. Aside from circulating books, and furnishing facts in reference work, the library encourages and assists all efforts to an educational end, and the advancement of our people in the city. The people feel that the library belongs to them, and that it may be used for anything that makes for their welfare."

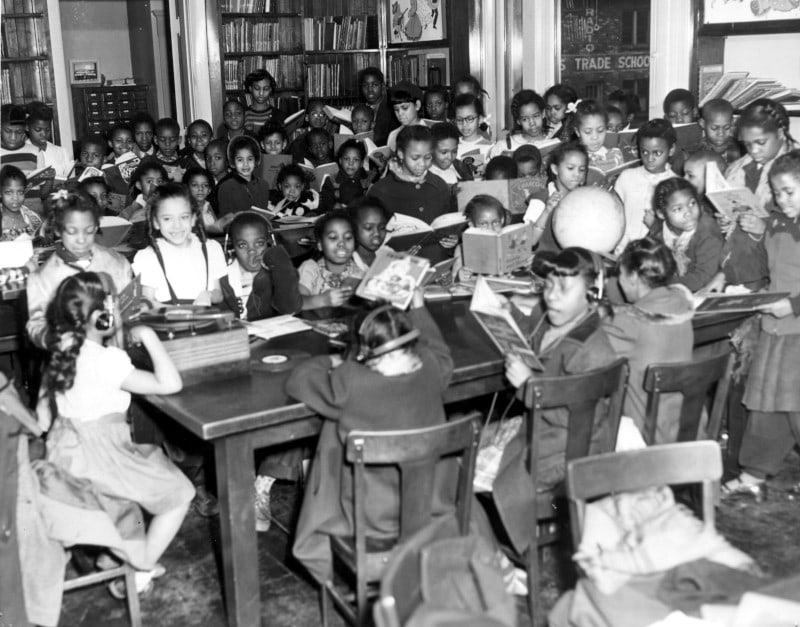

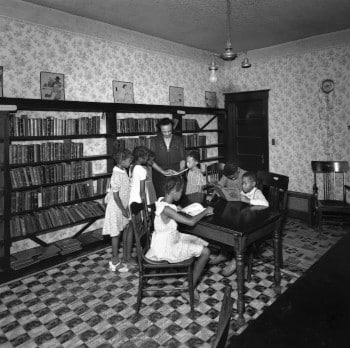

Blue's work began with a main focus on children and developing an expanding pool of young readers. He organized a Children's Department placed under the supervision of Mrs. Rachel D. Harris. Together they developed special entertainments, story hours, debate and reading clubs which proved successful and meaningful to the lives of black children. National African American poet and local educator, Joseph S. Cotter each year sponsored a children's storytelling contest, presenting cash awards and a Cup to the winners, who received statewide and even national attention.

And there was the prominent Douglasss Debating Club for high school boys who researched and argued such topics as whether "The Right of Suffrage Should be Extended to Women" or whether "The North American Indian has a Greater Opportunity for Development than the Afro-American." The young men who participated in these kind of activities went on to enroll in prestigious universities. Also in the first decade of the library's founding, Blue and his team would build an extensive collection of African American history, literature and significant writings. Literary clubs, story hours and other educational activities sponsored by the Library are as popular by the Library are as popular and widely supported by different users in the community today as they were decades ago.

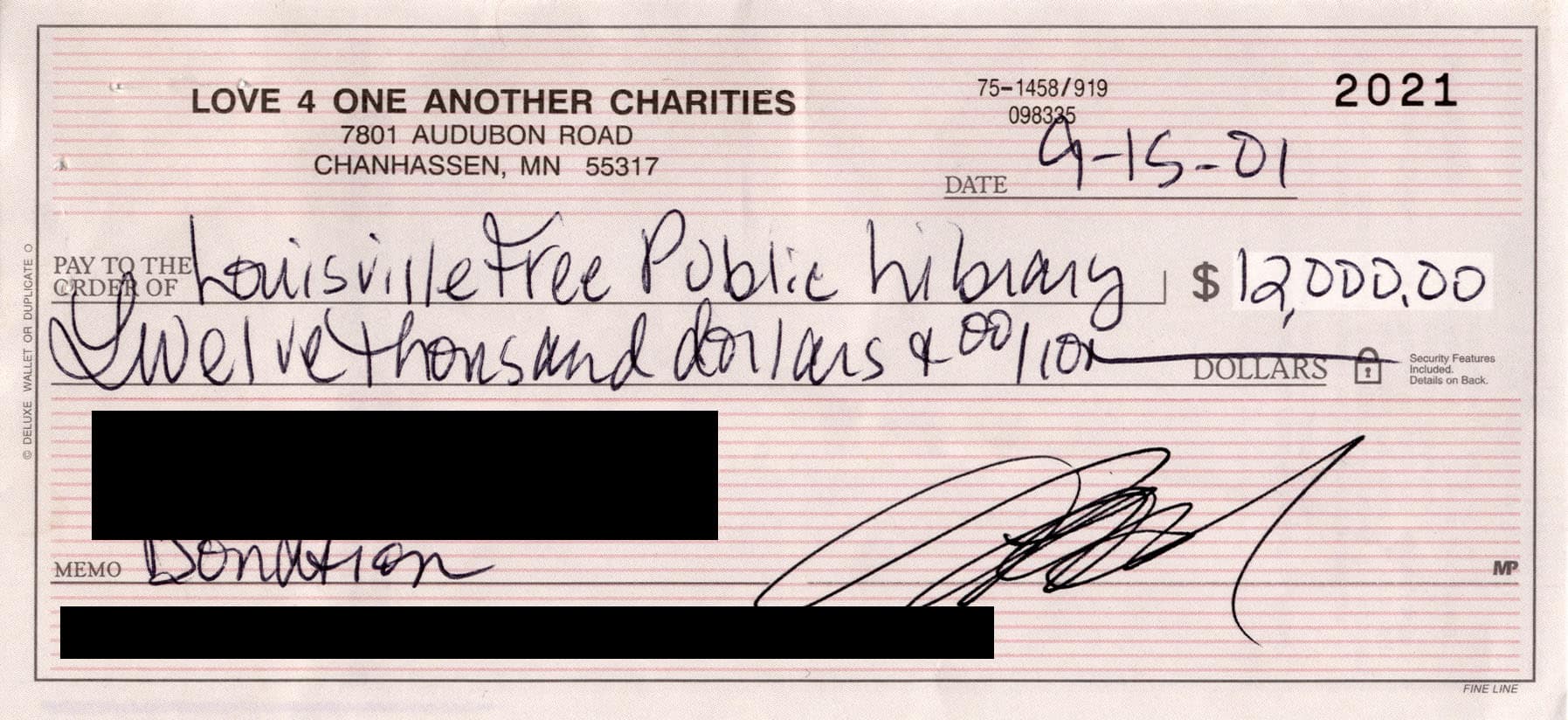

The story of the Louisville Western Branch Library is a story that continues to inspire and motivate all of us to use and offer our support to what has now become a landmark in our community. It is a treasure-house of thought and ideas -- where everyone has equal access to the power that is derived from knowledge.